Darrel's Immigrant Ship Page

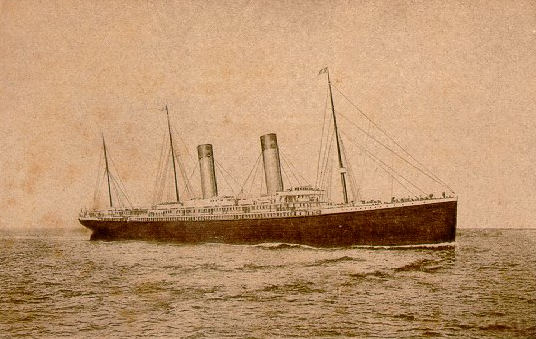

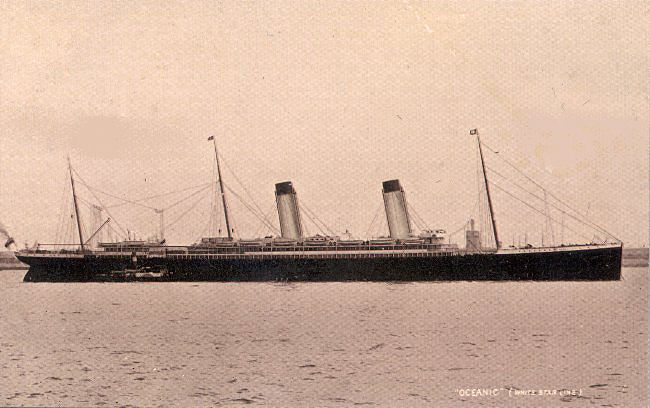

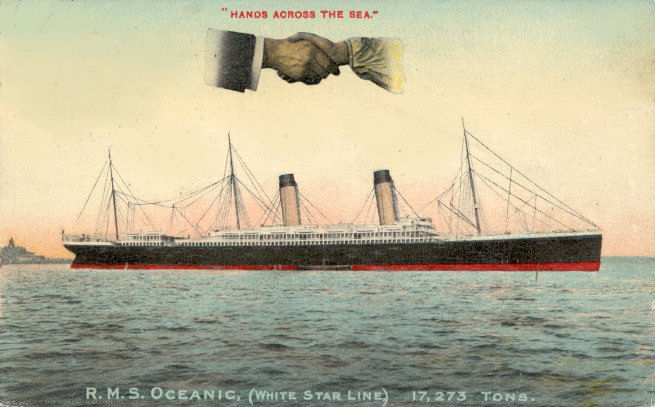

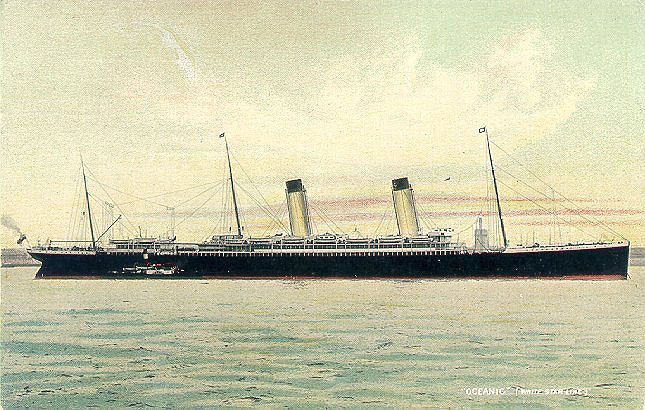

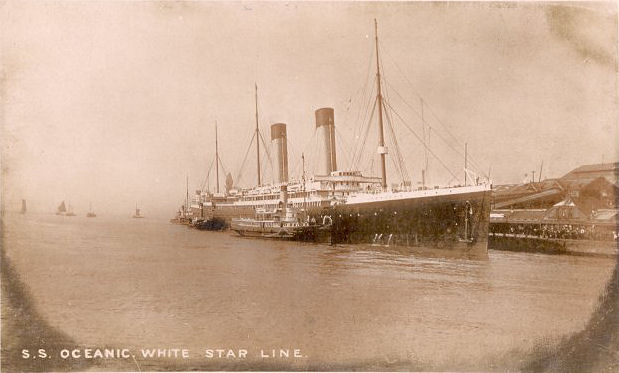

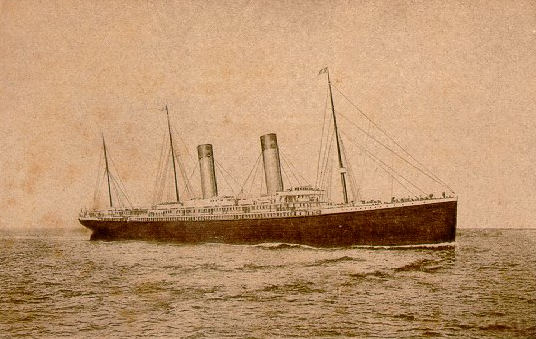

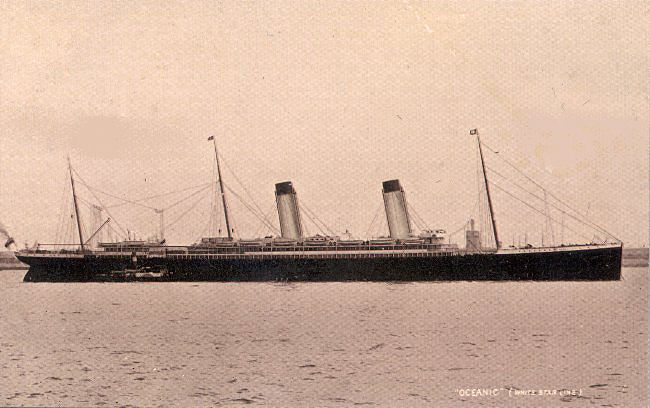

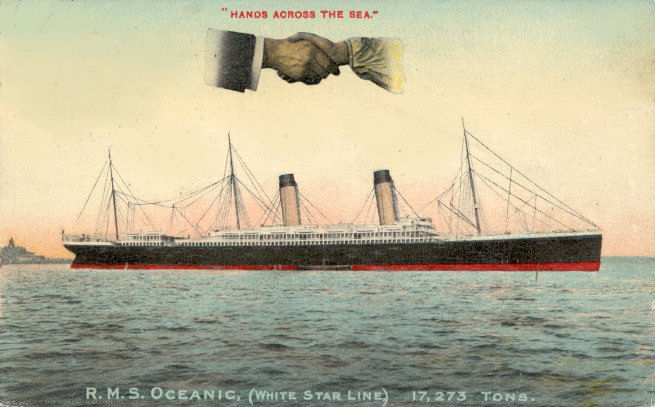

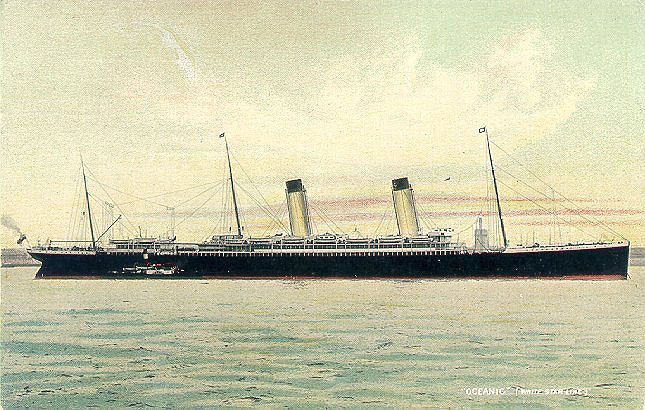

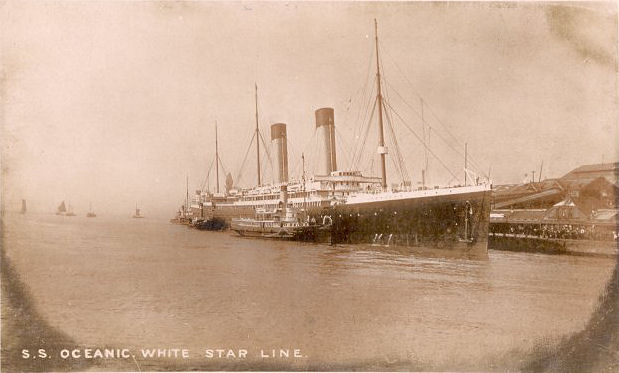

RMS Oceanic

1899-1914 (1924)

The second ship of the line

to be named after the company, Oceanic was launched from the ways of

Harland and Wolff on 14 January 1899. Her construction had been partially

subsidized by the Admiralty, thus her decks were strengthened to accommodate gun

mounts, coal bunkers and bulkheads were placed for maximum protection from

gunfire, specific speed and cruising ranges were met, and passenger spaces were

easily convertible into spaces for troop transport. Nonetheless, Oceanic's

size, sleek appearance, and luxury gave her titles such as "Ship of the Century"

and "White Star's Millionaire's Yacht."

Her appointments surpassed

the standards of luxury for her time. Her first class dining saloon could seat

over 400 in one sitting and its ceiling was adorned with a 21 square foot dome.

The saloon was lit from a row of oversized portholes on each side of the ship.

Where there were no portholes, there were electric lamps. In total, Oceanic

had 2,000 electric lamps. Another feature of the ship that was adored by her

passengers was the library, which many thought was the most beautiful of her

rooms, which was topped with a beautiful glass dome. She could carry 410 in

first class, 300 in second, and 1,000 in steerage.

She was delivered to White

Star on 26 August 1899 and would remain the largest existing ship in the world,

the first to surpass the length (although not gross tonnage) of Great Eastern,

until the arrival of Celtic in 1901. Oceanic's maiden voyage

began on 6 September 1899, on the Liverpool to New York run. While Oceanic

was a fast ship, averaging 18.96 knots on reduced power on this voyage, she

never broke the record to take the Blue Riband. It is possible that she was

planned to be a record-breaker, but for some reason, possibly vibration, never

did. Instead, she was the precursor of White Star's slower, larger, and more

luxurious "Big Four," consisting of Celtic, Cedric, Baltic,

and Adriatic.

On 1 September 1901, because

of low visibility due to fog, Oceanic rammed and sank the British coaster

Kincora off Tuskar, killing seven.

Even with the introduction

of the "Big Four," Oceanic remained the ship of the line until the

arrival of Olympic in 1911. Her speed and luxury made her very popular

with sophisticated travelers, among them International Mercantile Marine (IMM)

bankroller, Junius Pierpont Morgan.

A mutiny onboard occurred in

1905, resulting in the convictions of 33 stokers. Even with incidents such as

these, White Star director J. Bruce Ismay made sure that Oceanic was

repaired and back in tip-top shape as soon as possible as she was the last White

Star liner launched during his father's lifetime. Originally, Oceanic

was to have a sister ship, to be named Olympic or possibly Gigantic,

but this sister was never built, and the name Olympic would be reserved

for another, much larger and more luxurious ship.

Even with the introduction

of the "Big Four," Oceanic remained the ship of the line until the

arrival of Olympic in 1911. Her speed and luxury made her very popular

with sophisticated travelers, among them International Mercantile Marine (IMM)

bankroller, Junius Pierpont Morgan.

A mutiny onboard occurred in

1905, resulting in the convictions of 33 stokers. Even with incidents such as

these, White Star director J. Bruce Ismay made sure that Oceanic was

repaired and back in tip-top shape as soon as possible as she was the last White

Star liner launched during his father's lifetime. Originally, Oceanic

was to have a sister ship, to be named Olympic or possibly Gigantic,

but this sister was never built, and the name Olympic would be reserved

for another, much larger and more luxurious ship.

White Star's eastern terminus for

the North Atlantic route was moved to Southampton in 1907, and 19 June that year

marked Oceanic's first voyage on the Southampton to New York run. In

1911, during a thunderstorm a bolt of lightning struck the ship's foremast. The

impact was felt all over the ship. A nine-foot fragment of the mast then

crashed down on deck, sending splinters all over the open bridge and narrowly

missing the glass dome of the library. Her wireless was also put out of

commission for a short time.

The Great Coal strike of 1912

resulted in the temporary laying up of several I.M.M. ships, Oceanic in

Southampton being one of them, so that the new liner Titanic would have

enough coal for her maiden voyage. When Titanic left Southampton on 10

April 1912, then the largest liner in the world, the new liner's displacement

pulled Oceanic out of her berth so far that a 60-foot gangway linking her

to her pier fell into the sea. The ship tied just abeam of Oceanic,

New York, was pulled out of her berth, breaking ropes attempting to hold her

back, and almost collided with Titanic. Days later, while at sea

Oceanic would pick up a lifeboat (collapsible A) from the ill-fated larger

liner finding three bodies so badly decomposed that they had to be buried at sea

on the spot.

When Great Britain declared

war on Germany in August 1914, Oceanic was at sea, going from New York to

Southampton. When she reached the Irish coast, she was greeted by two Royal

Navy cruisers and escorted for the remainder of the voyage. She was quickly

converted to war service and commissioned as H.M.S. Oceanic upon her

arrival at Southampton. The conversion would take two weeks. She would be

captained by her master of two years, Henry Smith (unrelated to Titanic's

E.J.), and the Royal Navy's own William Slayter. Smith would be in command in

an advisory capacity, but Slayter was in nominal command of the ship and crew.

An unsubstantiated rumor

stated that Oceanic would be patrolling an exotic (and safe) Far Eastern

port, resulting in several of her civilian crew remaining aboard. Merchant

seamen who remained were joined with naval officers and ratings, resulting in

several misunderstandings between the two groups initially. When Oceanic

left Southampton on 25 August 1914, however, her destination would not be

Bombay, Rangoon, or Hong Kong, but rather north to Scapa Flow to join the 10th

Cruiser Squadron. There must have been some disappointment onboard when this

was found out.

Arriving at Orkeny, Oceanic

was sent to patrol the Western Approaches, west of Fair Isle. She then went to

make a courtesy call at Reykjavik, Iceland and returned to Scapa Flow where

gunnery practices for her inexperienced crew began. Several of the ship's

civilian crew was now composed of several Shetland Island fisherman.

Oceanic was to patrol

an 150-mile stretch of sea between Scotland and the Denmark's Faroe Islands,

making sure that passing ships' cargoes and passengers did not contain

contraband or German sympathizers.

So that gun crews watch

endings would not end at each morning's general alert, Slayter ordered the

ship's clock set back forty minutes. Now the ship had two times, Greenwich Mean

and ship's, for the ship's two captains and three crews. Needless to say, more

confusion resulted.

Informally, Smith and Slayter

agreed that the former would be in command during the day and the latter at

night, even though the two were still at odds over how to manage the ship.

Slayter, being of the Royal Navy, was in overall command. Slayter had

Oceanic search for German submarines and patrol craft around the island of

Foula. She would spend much of her time on zigzag courses to evade German

submarines. The duty of recording the course changes would be handled by David

Blair, originally second officer of Titanic, but was displaced with the

"demotion" of officer Charles Lightoller, who incidentally was now Oceanic's

first officer.

Foula was sighted on 7

September 1914, and she continued to zigzag despite thick fog. The fog cleared

up the next morning. By this time, Blair calculated that Oceanic was

well south of Foula. Slayter then ordered Oceanic on a course to take

her back to Foula before retiring. Blair made the calculations, and after that

was done, he too retired for a nap.

Smith arrived to look over

the chart while Blair napped and concluded that Oceanic was fourteen

miles to the south and west of Foula. Fearing that their course would result in

the ship's running aground on the reefs around the island, Smith ordered a

course change to the west to the open sea without consulting Slayter. When

Blair awoke and reported for duty, he suggested that soundings be taken to

determine the exact position of the ship, but Smith vetoed the idea.

Half-an-hour later, Foula was sighted dead ahead. Blair, either because the

complicated calculations he had to make or because of fatigue, had plotted

Oceanic off course. Smith turned the ship several points to starboard to

avoid the southern end of the reef known as Da Shaalds (The Shallows) and bring

the ship into a narrow channel between reef and island, the latter of which

Smith estimated to be four miles off.

Hearing the lookout's cry,

Slayter rushed to the bridge. Seeing that the ship was closer to Foula than

Smith had thought, Slayter ordered a sharp turned to starboard to leave the area

as soon as possible. At that moment, with a large amount of grinding,

Oceanic was pushed into Da Shaalds, stern first into the reef. The next

tide, instead of freeing her, drove her further into the reef.

The Aberdeen trawler

Glenogil and the Royal Navy's H.M.S. Forward put lines around

Oceanic, but Oceanic was pushed in much too far. The tow lines

snapped and Oceanic stayed right where she was. Soundings then showed

that the double bottom was so badly breached that even if she were to be freed,

she'd sink. Orders to abandon ship were given late that afternoon. By evening,

all of the ship's 600 crew members were evacuated without incident, ferried to

other vessels standing by via lifeboats. She was declared a total loss on 11

September at age fifteen.

For the next three weeks, the

Admiralty salvage vessel Lyons recovered all guns, all but one of the gun

shields, and most of the ammunition among other naval fittings. There was a

long period of quiet around Foula afterwards, but then an incredibly fierce

storm struck on 29 September. On the morning of 30 September, Oceanic

had disappeared.

At first, it was thought that

the storm had lifted Oceanic off the rocks and carried her to deeper

waters to sink, but it was later discovered that the storm had pounded the ship

against the rocks so that she was reduced to smithereens. Her remains lay

scattered in relatively shallow water. Breaking-up on the spot would be

completed in 1924.

Smith, Slayter, and Blair

were all court-martialed. Comparing Oceanic's log and the ship's last

movements as witnessed by the inhabitants of Foula and noting their

inconsistencies, Smith and Slayter were exonerated and Blair was let off with a

mild reprimand. The hearings resulted in changes in the armed merchant

cruisers' administration, and the mercantile officers were given more

responsibility.

Copyright © 2003 Darrel R. Hagberg

All rights reserved.

Updated on July 23 2006